Mandelbrot, Boyd & Musashi: Part 3 - Risk

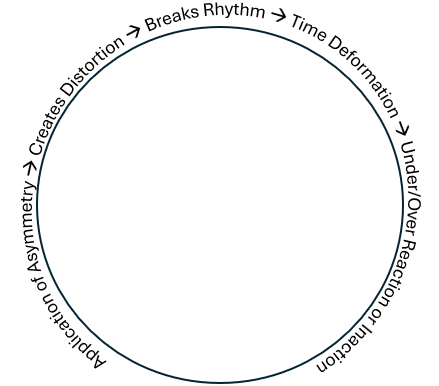

Previously in Part 1-Fractals we discussed operating at a faster tempo would yield a faster decision cycle. This led to the conclusion of the importance of guarding against things that might mess with one’s perceptions - slowing down the ability to act or re-act. In Part 2-Asymmetry we discussed the asymmetric cycle where a symmetric force is countered with an asymmetric force and this creates an imbalance - a disruption in the rhythm. This disruption in rhythm introduces a vulnerability that can be exploited. This could be an exploit that has physical dimension or an exploit that is temporal - something that disrupts the decision cycle. This is the footballer fake out mentioned in Part 1-Fractals or the Spartans slow reaction to the Thebans asymmetric formation described in Part 2-Asymmetry. For Part 3, I will be looking into risk. For every decision in the cycle carries some level of risk that needs to be considered.

Writing about risk is problematic because there is a plethora of existing material that has provided an endless number of perspectives on risk. No matter how much one reads, learns, or experiences inform views of what risk is and how to measure and mitigate it - there exists some alternative process - there is not one universally agreed methodology. To start, let us define risk.

Risk, a situation involving exposure to danger; a person or thing regarded as likely to turn out well or badly, as specified, in a particular context or respect; a person or thing regarded as a threat or likely source of danger; expose (someone or something valued) to danger, harm, or loss; act or fail to act in such a way as to bring about the possibility of (an unpleasant or unwelcome event); incur the chance of unfortunate consequence by engaging in (an action) (Lindberg, Stevenson, 2010, 1507). The key takeaway is that risk happens when an action is taken, one that has some ambiguity to outcome, whereby the result may be undesired.

Organizations take, in some cases, an inordinate amount of time assessing risk to mitigate it. It is one of the reasons why people are forced to spend hours in countless meetings throughout the day. Consider the company going through the process of making a key decision that will impact their future operations. The final decision on whether to proceed is set for a meeting with the company leadership. This meeting will ultimately decide if risk will be taken in pursuit of the defined objective (whether that is a new product launch, acquisition, et cetera). One meeting, yet this one meeting will generate dozens more at every level of the company. Every level of the company that is funneling up information to that one meeting will put effort into identifying, assessing and mitigating risk. When information is pushed up, this will generate question back down, driving more engagement - all to assess and mitigate risk so ultimately when the company leadership makes the decision, that decision is informed of the risks. No one wants to be caught “flat footed”, and everyone wants to get “out ahead of the problem” to look effective to their boss, but it is all about mitigating risk. This is the reason why countless individuals find themselves in 10 hours of Zoom meetings each day - risk assessment and risk mitigation - to ultimately provide the perception that the manager is ahead of the problem and reducing risk for their boss.

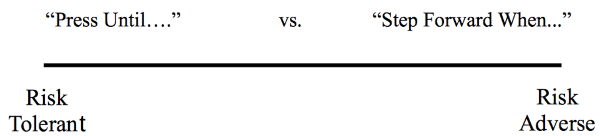

What do I use to assess risk? I prefer to keep things simple as one can drive themselves into analysis paralysis (or endless meetings) attempting to quantify risk. I also believe that risk happens at the tactical or micro level despite the decision to take risk being made at the strategic or macro level. Therefore, one needs a way to quickly assess and act. I like to use Conley’s Spectrum of Risk (David Conley, pers. comm.). On the left side of the spectrum exists risk tolerance: “press forward until...” and on the right side of the spectrum exists risk aversion: “step forward when...” What does this mean exactly? Risk tolerant means that we are on the offensive - leaning forward on the project until we hit a point where we cannot continue. Risk aversion means that we are on the defensive - acting only when the threat requires action.

Conley’s Spectrum of Risk

Conley’s Spectrum of Risk

A more common framework for risk assessment would step through the following questions:

- Risk to What?

- Risk from What?

- How much Risk?

- How much Risk is ok?

- What to do about the Risk?

Of course, before one can use the spectrum or any other assessment tool, one needs to define what is an acceptable risk level (this is done in the How much Risk is ok? step above). The acceptable risk level is the point where the risk is acceptable to the organization and anything beyond this point is unacceptable. The final decision meeting referenced above is the event where the risks outlined are accepted by the principals of the company. Certainly, when Apple’s leadership gave a green light to the Apple Vision Pro, they did so accepting a level of risk to the project’s ability to meet its objectives. This risk level, I suspect, is assessed regularly and influences decisions at Apple regarding the future of Vision Pro and any expansion of the VR product line. The risk level for VR is probably not the same for a more established product line such as the MacBook Pro. Risk levels need not be universally applied, they can be as granular as needed, and they can shift as the environment or situation changes.

If the hardest part of risk assessments is the initial actions at determining what the risk is, the second hardest is dealing with events that drive changes in the risk level and risk tolerance. What if the accepted risk level is shifted left (as in Conley’s Spectrum above) with high risk tolerance, but changes in the environment drives a need to shift to the right and lower risk tolerance? Similarly, a startup (or early adopter market product such as AR sunglasses) may be oriented toward a high-risk posture, but then the market matures driving a lower risk posture. How would this shift be recognized, tracked, and adjusted? In two words: clear criteria.

Risk tolerance is a metric based off perception. Risk capacity is a metric based off finite parameters.

Picture the following scenario: There is a humanitarian crisis developing around a civil war inside a country. The international community is rallying to respond not only in interests of assisting the local populace, but also in self-interest in extracting their diplomatic teams and other citizens living and working in the host country’s capital city. A decision is made to conduct an air evacuation out of the capital city’s international airport. Through diplomatic channels, the assessment is that any flights into the country to extract foreign citizens or deliver humanitarian supplies will be safe from attack by host country air defenses. The acceptable risk level has been set with the defined parameter that the host country’s air defenses lack the intent to interfere with the airlift package (military or civilian transport). What if this changes?

In this scenario, the airlift package would need to be supported by ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) assets that could detect a change in posture of the host country’s air defenses and then relay this change to the airlift package. The airlift package would then know that they exceeded the risk tolerance that was defined for the mission and be able to make the decision to abort. Without adequate and clear criteria - the airlift package would exceed the risk tolerance unknowingly. This does not just have to be a military operation to apply. A football game where the home team is up 27 to 10 and it is the start of the fourth quarter. The coach decides that a 17-point lead is an acceptable risk level to pull the starters and put in the second-string players. When the coach made this decision was there clear criteria on when risk tolerance would be re-assessed? What if the visiting team scores two touchdowns in 5 minutes of play bringing the lead to within a single field goal?

Any organization needs to have clear risk tolerances defined and be able to assess where on the risk spectrum they are through clear criteria. Clear criteria will tell the organization, or in this case, the football coach, when the team has moved from the point on the risk spectrum deemed acceptable to a point it no longer is. The coach could have stated criteria as follows: we will put starters back into the game if the visiting team is able to get within 7 points of us at any time in the fourth quarter or within 10 points of us with more than 5 minutes of play remaining or time sufficient for the visiting team to complete two possessions from end of the field to the other.

How do you identify and assess risk? For the football coach, they probably are conducting this process real time off visual information in the stadium supplemented by the voices of their coaching team heard through their headset, but what of a more ambiguous, unclear (and perhaps mundane) environment? Do you create a register listing the risks and determine the exposure to the risk by multiplying the probability of it happening with the impact (in time or some other metric) to the project? Do you transfer this register into a graphical risk burndown chart to visually see where risk is decreasing or increasing?

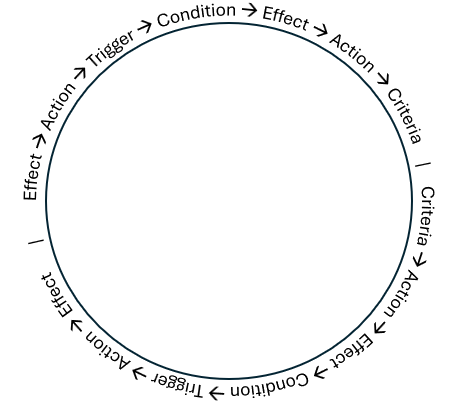

I suggest using the simple and straightforward Criteria Wheel below, it visualizes the process of defining clear and specific criteria. Without clear and specific criteria, the situation can arise where the perception that conditions are set but in reality, are not. Identify where inappropriate, ineffective effects are applied leading to unplanned outcomes and ramifications such as inadvertent risk escalation.

As an example, below is the application of the Criteria Wheel to a fictitious cyber event and working backwards from the desired ending point:

Effect (DDos attack ineffective)-> Action (Adversary attacks)-> Trigger (network ready)-> Condition (network hardened)-> Effect (vulnerabilities removed)-> Action (patches applied)-> Criteria (identify specific network layers to protect, specific vulnerabilities to patch)

Having clear criteria to understand where one is on the spectrum of risk is an important step, but just as important is the ability to track this risk real-time. If you look up the term “battle tracking”, you will likely find some explanation that it is a tool to provide situational awareness of the battlefield and track the progress of the tactical objectives. Battle tracking is the key component of assessing risk real-time. For without it, knowing if the criteria for establishing the acceptable risk level is met will be problematic. Battle tracking will provide the who, what, where and relay this information to those that need to know.

Let us put this together. First, we determine where we are on the spectrum of risk - the left side (risk tolerant) or right side (risk adverse). Startup project? Probably high risk on the left side. Incremental update to a long-term stable and mature project? Probably low risk on the right side. Second, how do we define the acceptable risk level we want to be at on the spectrum? Using the Criteria Wheel, we define criteria to set the conditions that allow us to operate at the desired risk level and no higher. Third, how do we know if the criteria are met or that we have exceeded our risk level? We “battle track” the project, checking off criteria as it is met, noting when it is not, and getting that information to the stakeholders and teams that need to know.

This drives a detour into discussing capacity and contingencies - specifically, building capacity versus building contingencies. When we conduct risk mitigation, we are building contingencies (this is the What to do about the Risk? from the risk assessment steps listed above). If-then-else type statements designed to mitigate a defined risk. For the football coach and their assistance coaches, they are always building contingencies to counter the visiting team’s offensive and defensive lines. The other scenario, of an airlift package knowing when the host country’s air defenses have changed their intent driving increased risk - this is more ambiguous and difficult to discern due to the fog of war (as would entering a new and undefined market space). Defining contingencies can quickly outpace the ability to implement said contingencies due to the sheer number of potential variables (due to the level of ambiguity of the environment).

Why do we have contingencies in the first place? You do not know what you do not know. Every operational plan will have ambiguous or unknown information. These unknowns must be addressed in the planning cycle and the first step is making certain logical assumptions. These logical assumptions are determined after some critical analysis is applied to these unknowns. What if our assumptions are wrong? What do we do then? One aspect of the planning cycle is discussing what happens when these assumptions are not met. This is usually done during the analysis and wargaming of the proposed game plan where the primary plan is tested against possible contingencies.

For example, maybe you assumed how the host country’s air defenses would react to the influx of aircraft and now are asking what if you are wrong – what do you do? You did not expect your actions during the evacuation to trip the air defenses to start shooting at the aircraft. The football coach did not expect the visiting team to score two touchdowns in the fourth quarter to bring the game to within a field goal of a tie. Now, you must figure out the contingency plan. If the air defenses start shooting, the airlift package changes their ingress or egress routing to avoid the air defenses (if they do not abort outright). The football coach brings back in his starters or instead of playing a defensive ‘burn the clock down’ strategy - goes on the offensive to score points. (this is the coaching strategy of “to not lose the game” versus the coaching strategy of “to win the game” - fight till the clock stops, never give up, maximum effort…this is the way).

The downside of contingency plans is you can what if things into a black hole. The contingency plan can become so elaborate and spaghetti code-like that the execution bogs down. What is the alternative? Building Capacity. What does building capacity mean? It means we build the capability to flex and absorb the unknown. This is not the same as being an athlete. This is a term used in my world where when things go sideways - we become an athlete with no alternate and no contingency (NANC) - tackling the problem in real time. A plan that lacks contingencies will typically result in the team needing to be athletes during execution when risks change. Building Capacity first requires clear and specific criteria (see above).

It would be a fallacy to think that building Capacity requires more of everything - more aircraft, more skilled football players. Building Capacity is not about building a deeper bench to draw from when things do not go as planned and changing risk levels. Rather, it is the ability or power to do - to experience and understand - to adapt (Lindberg, Stevenson, 257). A football team that has Capacity has a greater ability to experience the events transpiring on the field, understand them, and adapt or flex meeting the change - mitigating the risk. This is the quarterback calling plays real time without reference to the sideline. This would be unworkable without clear criteria framing the conditions, actions and effects. Think of building the Criteria Wheel as creating blueprints, now the construction crew has a framework reference to be able to discern variations from the blueprint. The speed at which the crew can discern these variations, react to and mitigate, the faster their decision cycle will be. This connects back to the original discussion of decision cycles where we channel Boyd and Musashi.

The decision cycle is disrupted by applying an asymmetric counter, this is an unexpected action; this creates distortion where the perception filter of the opponent is altered; this drives time deformation bunching into irregular segments driving time scales to be perceived differently thus slowing decisions (the variability of the multi-fractal environment); leading to the opponent under/over-reacting or inaction. The football player fakes out the defender, where the defender either fails to react appropriately or reacts in the wrong direction, allowing the football player to score.

When we have Capacity, we can avoid things that disrupt our perceptions - the ability to process information and adapt at a time scale that drives disruption in the opponent’s decision cycle. In effect, we are operating at a faster tempo and be able to effect change faster to mitigate changes in risk. This is the football coach perceiving a change on the field in the visiting team’s posture and actions before they score that touchdown. Not surprisingly this comes back to understanding risk. When the visiting team, down by 17-points, starts to take risks by performing no-huddle offense (getting inside the home teams time scales), flea flickers (disrupt perceptions), or 4th-and-long conversion plays - these tactics should highlight that the visiting team has changed their acceptable risk level, which should trigger the home team to reassess theirs. If the opposing team scores and they proceed to perform an onside kick - they are embracing risk - failing to respond will elevate risk for the home team (if not already). This is where a foundation of clear and specific criteria will help the football coach (and team) to better process real-time changes, understand the risk implications, and react accordingly.

I have presented risk in the context of decision cycles. Initially discussing Conley’s Spectrum of Risk as a potential tool to assess risk tolerance, then discussed defining clear criteria using the Criteria Wheel and then discussed the concept of Capacity. Connecting this back to the concepts discussed in the previous essays from asymmetry to multi-fractal time deformation and the writings of Col Boyd and Musashi. Where do we go from here?

I think the key to all of this - the decision cycle and the ability to operate at a faster tempo and thereby avoiding things that disrupt our perceptions - ultimately requires an understanding of consciousness. Consciousness is the state of being awake and aware of one’s surroundings; the awareness or perception of something by a person; the fact of awareness by the mind of itself and the world (Lindberg, Stevenson, 369). I do not think understanding consciousness is an understanding of Descartes:

“dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum”

Rather, to understand consciousness is to understand and perceive that without consciousness there is no time. If time is the measurement of change, for there to be change, there must be an observation of the before and after state (the change) and without consciousness there are no observable events (or states). Think of the mind as a series of events - conscious observations. This can be seen in the observations of an electron, the observation determines if the electron is a particle or a wave. What am I saying? That time exists because of consciousness, without it, there is no observable time.

The mind is measuring time through the observation of the present and is storing, cataloguing events (or states) to inform the present and predict the future. We learn to judge distances and closure rates through experience as we learn to drive (or fly) by using past impressions to calculate the future position of the observable objects around us based on the given parameters. In other words, the football defender reacts based on past observations that are selected based on the perceived observations of the ball carrier’s actions. One’s mastery of consciousness drives one’s mastery of perceptions -> making one a maestro of tempo and rhythm. Ergo Decision Cycles.

Where do we go from here? My initial thought is that this is where physicality enters the room. Physical conditioning, diet, meditation, actions to build the body and purify the mind to combat distractions. Distractions that prevent the discernment, or sensing required to be at a conscious state to operate in and out of an opponent’s time scales.

If you always assess risk with every single decision regardless if it has strategic (negative) ramifications, two things happen. First, you see risk in everything. Second, your risk spectrum gets distorted and trends toward risk aversion (step forward when…). Stop doing that. Or you will be exposed to far greater strategic risk from a competitor with just a bit more risk tolerance than you have.

__________

Boyd, Colonel John. 1976 “Destruction and Creation.”

Conley, David. 2017. Personal communication, 11 June 2017; Reynolds, Jeremy. 2017. “Conley’s Spectrum of Risk, 2017, Digital Image.

Lindberg, Christine, Stevenson, Angus, ed. 2010. The New Oxford American Dictionary, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mandelbrot, Benoit. 2006. The (Mis) Behavior of Markets. New York: Basic Books.

Musashi, Miyamoto. 1992. The Book of Five Rings. trans. Bradford J. Brown, Yuko Kashiwagi, William H. Barrett, and Eisuke Sasagawa. New York: Bantam Books.

Rovelli, Carlo. 2017. The Order of Time. trans. Simon Carnell, Erica Segre. New York: Riverhead Books.

__________

© 2025 Jeremy Reynolds, all rights reserved.

Back to Blog Index

decisions