Mandelbrot, Boyd & Musashi: Part 2 - Asymmetry

Previously in Part 1-Fractals we discussed operating at a faster tempo would yield a faster decision cycle. This led to the conclusion of the importance of guarding against things that might mess with one’s perceptions - slowing down the ability to act or re-act. I alluded to in that essay a connection with asymmetry. What seems like forever ago, but was only about eight years, I wrote a research paper dealing with asymmetric threats and how to carve out a limited window in both time and space for air superiority. The argument being asymmetric threats (think anti-access and area-denial advanced threat missile systems that prevent maneuver into and within a theater of operations) would make achieving permanent air superiority unlikely and it is better to think in terms of air superiority localized to a specific geographic three-dimensional space for a specific time window for exploitation of a specific effect. This temporary lane concept was derived from my research into symmetric and asymmetric threats. In this essay I connect the idea of how asymmetry relates to decision cycles and other concepts such as classical mechanics.

I have been a student of Colonel John Boyd long before I became a practitioner and (fellow) patch wearer. It was one of his papers that gave me the spark to see the connection between what appear to be unrelated principles of different scientific genres. Colonel Boyd wrote about order and disorder, and he connected this to such things as the Heisenberg’s Principle or the Second Law of Thermodynamics and then back again to decision models. This paper encouraged me to consider other concepts and principles when searching for a way to address the asymmetric threat problem and air superiority. I came up with classical mechanics and Newton’s Third Law of Motion, but first let us start with the concepts of asymmetry and symmetry.

There is a dictionary definition of asymmetric warfare that I do not want to confuse with the asymmetry I am discussing in this essay. That definition is warfare involving surprise attacks by small and simply armed groups against a modern high-tech weaponry equipped nation (Lindberg, Stevenson, 100). Also, discussing asymmetry should start with what symmetry is so as to understand the departure. Symmetry is the similarity or exact correspondence between different things, the quality of being made up of exactly similar parts (Lindberg, Stevenson, 1760). In contrast, asymmetry is having parts that fail to correspond to one another in shape, size or arrangements or having parts or aspects that are not equal or equivalent (Lindberg, Stevenson, 100). Asymmetry is something that is different or unequal to what it is counter to.

Thinking militarily, two opposing forces, one unequal to the other, create a dissimilarity that makes balance difficult or impossible. Thinking like Bud Fox, two opposing prices, one the bid and one the ask, where if the dissimilarity is too strong creates a wall that places a barrier and manipulates the price in a determinate direction. Think of symmetry as being in balance and being the same thing or being made up of the same thing, while asymmetry is out of balance and made of dissimilar things. Two opposing forces, in symmetry with each other, could be merger of the bid and ask or two equally matched tank columns. In the first, this is good for the buying and selling of a stock, but in the second this symmetry is likely bad leading to a drawn out conflict resulting in at best a draw. It would be the same in the consumer electronics markets where two products do the exact same thing such as OLED TVs - the differentiation becomes perceived value for money (price-quality relationship). No clear advantage. Does this mean that a dissimilarity or lack of balance is a negative or positive?

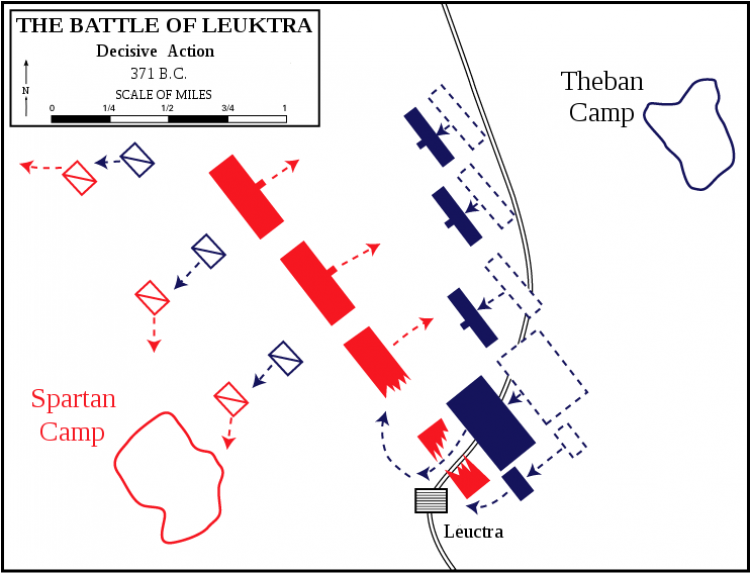

I imagine everyone has heard of the Spartans and the Battle of Thermopylae where 300 Spartans led by Leonidas made a last stand against the Persians. Little acknowledged was this last stand was supported by other Greeks to include the Thebans. A little over a hundred years later the legendary Spartans faced off against these same Thebans in the Battle of Leuktra. The historical details leading to this conflict are less important for this discussion, rather it is the application of asymmetry by the Thebans on the battlefield with their use of an imbalance and unequal force distribution.

The Thebans distributed their troops in an imbalanced manner, giving the Spartans the impression, that the Thebans had an inferior sized force. They deviated from warfighting tactics of the time and placed their strength to the left, while leaving their center and right forces small. The strength, the best soldiers, were normally placed on the right wing (the symmetric thing to do). The Thebans also made this left wing (column) much deeper in number of men to the Spartan’s right wing (column). The Thebans also placed their phalanx behind the light infantry and cavalry, something armies of the time did not do. This asymmetric troop formation that was contrarian to the traditional symmetry of a Greek troop formation created an imbalance or disruption on the battlefield and messed with the Spartan’s perception filters.

This disruption was a fake out - similar to the footballer fake out mentioned in Part 1 - Fractals. The Thebans unorthodox formations and deceptions of their strength led to an observation distortion for the Spartans. Uncertainty is introduced in the Spartan’s orientation and thus their decisions and reactions are incorrect to effectively counter the Thebans. The Thebans left wing smashed through the Spartan’s right wing and Spoiler Alert……the Spartans lost. A proper historian might argue this was simply because the Thebans had four times the number of men in their column than the Spartans did; however, if this was true then the Spartans should have recognized this numerical mismatch and compensated earlier enough to have some impact on the outcome of the battle (nevermind the fact the Spartans had roughly 4,000 more troops on the field). Yet, the point is not so much a granular breakdown of the battle, but the Thebans decision to employ something different, unequal, asymmetric instead of a traditional Greek formation that would have been in balance and symmetrical to the Spartan’s formation.

Perhaps this asymmetry concept is an advantage in adversarial confrontation, but not always preferred in other realms (trade imbalances for example). For consideration in the concept of decision cycles, asymmetry appears to be a key advantage in creating friction in an opponent’s cycle - regardless of if that opponent is a Sith Lord (or a 12-year-old pretending to be one) or football team. The Theban force was asymmetric in its organization and contents as opposed to the more traditional and thus symmetric Spartan forces. The Spartans incorrectly surmised this asymmetry as a disadvantage rather than a difference designed to exploit Spartan formation weaknesses. Even if the Spartans had picked up on what the Thebans were doing, who is to say they could have implemented a change. Sparta was not only dealing with asymmetric formation, but also asymmetric thinking about that formation. In other words, Sparta would have had to identify an asymmetric change to the physical formations and an asymmetric change in the thinking about the employment of the formations.

As alluded to earlier, where does classical mechanics fit into this discussion? Newton’s Third Law defined that for every object that exerts a force on a second object, the second object exerts a force on the first object. Now think about symmetric forces, equally opposed, in the form of two opposing navies. These two navies are equally matched in size, capability, lethality, manpower, skill and are likely to slog it out into a draw or war of attrition. How do two equally matched groups of surface warships stake out an advantage? Thicker armor plating, speed, longer range naval guns, radar – some of these are asymmetric and others simply symmetric variations. Perhaps the most asymmetric counter to the surface warship was the airplane. As we saw in WWII, some of the most feared battleships met their end at the hand of airpower. Or in the case of the numerically inferior Thebans, an asymmetric formation that in the end, nullified the Spartan’s right wing.

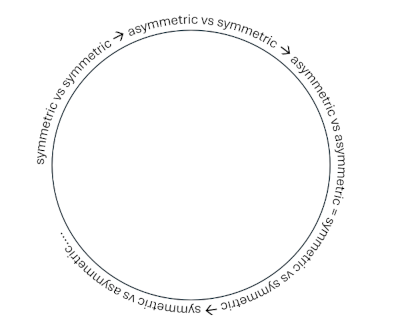

An asymmetric force is unorthodox and may appear weaker, but capable of disrupting the balance. For example, the submarine was an asymmetric threat to the symmetric surface warship. In cases of symmetric forces countered by symmetric forces, where there exists a desire and capability to create an asymmetry, we see a cycle begin. The cycle starts with a disruptive capability, an asymmetry, that creates an exploitation, and results in an immediate advantage soon to be counter-balanced by new asymmetric force. The cycle of symmetric force versus symmetric force followed by an asymmetric force versus a symetric force and then an asymmetric force versus a new asymmetric force.

For the asymmetric submarine it was countered by depth charges (enabled by sonar), which is certainly disruptive to the submarine – it is asymmetric. This asymmetry continues within the submarine community where one submarine is quieter than another until a new ability to detect that quieter submarine leads to further development of an even quieter submarine. What was once asymmetric becomes symmetric once it has been effectively countered by a new asymmetry. Much like Newton’s third law, there is an object exerting force, only to be countered by an opposing force. Of note is that the Third Law of Motion used the term “equal” when describing the forces acting on both objects and using a basic application of this law, we could overlook this, but I think what an asymmetric force may be is not a superior or unequal force, but a different force. One out of polarity with the force it is opposing. In other words, the force is at a different rhythm to the force it is opposing. This difference is enough to create a mismatch between the two forces - an imbalance in their rhythms. Thus an unequal force within the confines of this asymmetry discussion is not necessarily unequal in force but in the quality of the force.

As discussed in Part 1 - Fractals, operating at a different rhythm and thus time cycle is attacking an opponent with a rhythm they do not expect. This asymmetric rhythm, in the context of Musashi, is not necessarily weaker, but it is disruptive of the balance. Balance is an even distribution, where different elements are equal or in the correct proportion. Balance is also a counteracting force or the stability of one’s mind (Lindberg, Stevenson, 124). This disruption to balance is the same as an asymmetry - it drives an unequal nature between the two opposing forces, but this is not necessarily an inequality in physical force, but an imbalance in the rhythm that creates an exploitable weakness. I think a specific encounter in Musashi’s travels may better illustrate this concept. Of note, this dual was written about in different texts, the most vivid being the fictional account by Eiji Yoshikawa. As such, there is some potential that this dual did not happen exactly as written, but I believe it is still illustrative of the concept.

To understand the context, it is helpful to understand the weapons being used. Musashi’s opponent was using the kusari gama, it is a chain connected on one end with a sickle and the other a weight. An attacker would be faced with the wielder able to parry their strikes with the chain and with the spinning weight – able to grapple the sword gripped hand to pull the attacker within striking distance of the sickle. This may not make much sense, so I will offer this reference. Indiana Jones would typically use his whip to repel an attack and then use the whip to wrap around a beam to make it across a pit. The kusari gama’s employment was in the latter, wrapping the spinning weight around the sword hand of an opponent thereby immobilizing the weapon and the opponent’s ability to strike and provide the leverage to pull them close to strike with the sickle end of the weapon. Of course, this would work against symmetric sword wielding opponents of the day that carried only a long sword - not necessarily those that practice niten ichi ryu.

In Musashi’s travels he met such a wielder of the kusari gama in the form of a man named Shishido (called Baiken Shishido in Yoshikawa’s Musashi). Musashi, yielding two swords, already had a potential counter to the kusari gama attack. If Shishido was able to grapple his long sword, he could parry the sickle attack with his short sword (or in the case of Yoshikawa’s interpretation, release his grappled long sword while maintaining some semblance of defense with his second sword). As explained in the Nito ryu o kataru, Musashi observed Shishido’s spinning weight and began to spin his short sword above his head. As he did this, he synced the spinning of the sword with the spinning weight. This technique would appear to match the rhythm of the weight. This sounds in contradiction to what Musashi wrote about operating at a rhythm the opponent would not expect, but in truth it was an unexpected rhythm to what Sushido expected an accomplished swordsman to do with their sword.

Whether it was the use of two swords or Musashi’s spinning sword that created the asymmetry matters less than the fact that it did create asymmetry. Musashi’s use of two swords was not very common for the time and alone would require Shishido to alter his tactics, but a spinning sword likely compounded this tactical problem by creating a distraction that needed mental energy to process its role in the tactical situation, further slowing down Shishido’s decision cycles.

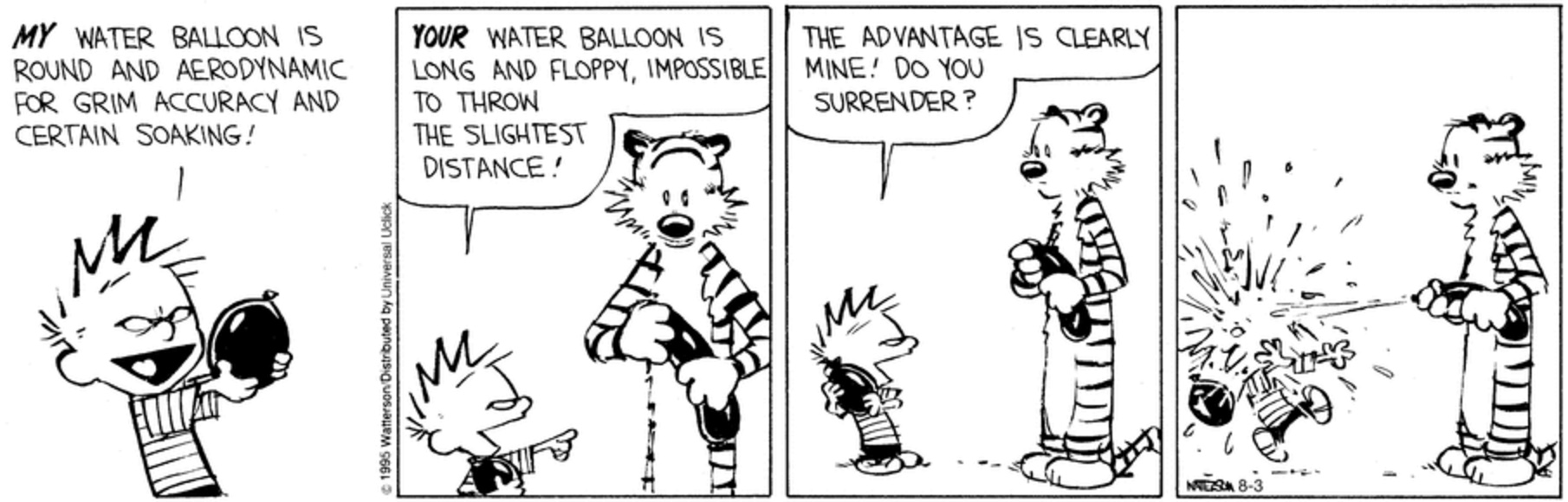

Asymmetry in practice: traditional water balloon vs water balloon innovation

Asymmetry in practice: traditional water balloon vs water balloon innovation

There is another theme emerging in this discussion of asymmetry and that of innovation. To innovate is to make a change to something established, to introduce a new method, idea or product (Lindberg, Stevenson, 896). When we take something symmetric and derive an asymmetric counter to it, we are innovating a new method, idea or product. A symmetric force in the form of a cellphone meets the asymmetric force of a smartphone and everything changes. Decision cycles where the passing of information was done first from a fixed location with a traditional land-line phone, then to a mobile phone speeding up the passing and processing of this information, and then again with a smartphone. Where the smartphone increased the speed of passing and processing information, but also the sourcing of that information and it also increased the pathways that the information could be transmitted and distributed into different applications (phone call, text, email, apps) creating a dramatic change in decision cycles. Just consider the buying and selling of a stock from the 1980’s to today - the speed that information can flow about a company, the real-time stock quotes, real-time sentiment (social media) and the ability to place trades real-time on a smartphone. Gone are the analog days of researching the stock by mailing off for their quarterly report and then calling your broker up to place a market order for a block of shares.

I have presented the concept of asymmetry initially from the framework of military application; fundamentally, asymmetry applies to everything - it can be the game changer in a person’s daily routine or what drives innovation and market share for a company. One just must connect the dots.

Where do we go from here? Discussions about decision cycles and the application of asymmetry to disrupt an opponent, whether that opponent is an individual, corporate adversary or nation-state, cannot happen without some discussion on risk. Every decision in the cycle carries some level of risk that needs to be considered. This leads us into exploring risk in Part 3.

__________

Boyd, Colonel John. 1976 “Destruction and Creation.”

Mandelbrot, Benoit. 2006. The (Mis) Behavior of Markets. New York: Basic Books.

Musashi, Miyamoto. 1992. The Book of Five Rings. trans. Bradford J. Brown, Yuko Kashiwagi, William H. Barrett, and Eisuke Sasagawa. New York: Bantam Books.

Cartwright, Mark. 26 June 2013. “Battle of Leuctra,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. webpage https://www.worldhistory.org/Battle_of_Leuctra/

Lindberg, Christine, Stevenson, Angus, ed. 2010. The New Oxford American Dictionary, 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

“The Battle of Leuktra,” Department of History, U.S. Military Academy, 2013, Digital Image. Available from: http://www.ancient.eu/image/1338/

Tokitsu, Kenji. 2004. Miyamoto Musashi: His Life and Writings. Massachusetts: Weatherhill.

Watterson, Bill. 1 July 1986. Calvin & Hobbes. comic strip, https://www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes/1986/07/01.

Yoshikawa, Eiji. 1971. Musashi. trans. Charles S. Terry. New York: Kodansha USA.

© 2024 Jeremy Reynolds, all rights reserved.

Back to Blog Index

decisions perceptions