40-Hour Workweek

“Human Beings Were Not Meant to Sit in Little Cubicles Staring at Computer Screens All Day, Filling Out Useless Forms and Listening to Eight Different Bosses Drone on About Mission Statements!” - Peter Gibbons (Office Space, 1999)

The 40-hour workweek is a relic of the Industrial Age and yet it still is the driving framework and metric for work in the Information Age. Why are salaried knowledge workers’ performance measured in hours? To better understand the ‘why’ I needed to investigate the genesis of the 40-hour workweek.

The 40-hour workweek draws its origins in a push for an 8-hour workday by labor organizations after the Civil War. The first legislative mandate passed in Illinois on May 1, 1867, and in May of 1869 was codified in law for federal employees by President Grant (Ward and Lebowitz, 2022). This of course at a time when the workweek spanned from Monday through Saturday. Sunday was the only day off and considered to be the last day of the week and is where the term weekend comes from. So, I suppose when asking a colleague how their weekend was - I am technically only asking them how their Sunday was.

As best I could find, the first five-day workweek in America occurred in New England at a factory trying to accommodate the religious beliefs of Jewish workers (Sopher, 2014). Since the Jewish sabbath is Saturday, the Jewish workers worked on Sunday, which offended the Christian employees that saw Sunday as the sabbath. The mutual offense led to the compromise awarding a two-day weekend and this new five-day workweek soon spread to other factories. Perhaps the most well-known implementation was by Ford Motor Company in 1926 where their factory floor ran on a 5-day 40-hour workweek. The Great Depression further helped the spread of the idea as the shorter workweek (and hours) was seen as a solution to under-employment. In 1938, thanks to the 75th Congress, the Fair Labor Standards Act introduced overtime pay by limiting the normal (pay) workweek to 40-hours (Ward and Lebowitz, 2022).

The 40-hour workweek is also a misnomer for many workers. In a Gallup poll, 39% of respondents said they worked more than 50-hour workweeks (Saad, 2014). The question is why? Is the workload too much to fit into 40-hours? Are individuals putting in extra hours to impress and earn promotions? Are individuals work-alcoholics who find status and self-worth from working endlessly?

Extroverts in search of human interaction and camaraderie? Introverts seeking the solitude of an empty after-hours work environment? Individuals forced to work long hours because they report to work-alcoholics that lack work-life balance? People that have eight bosses all named Bob because they work at a company with a matrix organization? I feel I have encountered almost all these types of individuals. Regardless, there are likely numerous reasons and variables playing into the numbers due to the diverse nature of industries and job roles resulting in varying work patterns. The fact remains that the 40-hour workweek remains the standard framework for American offices for compensation.

An industrial worker provides physical energy that produces a physical product. When a Ford Model T rolls across the assembly line every 93 minutes, the number of hours worked in a day determines the number of Model Ts that can be generated (Detroit Historical Society, n.d.).

A knowledge worker provides intellectual energy that produces a virtual product (and possibly contributes to an eventual physical product). When the product is programming code or other forms of information exchange or creation – the quantity of time becomes less a factor in what a given day generates.

While it is true that companies create metrics to measure productivity (effort, activities, output, outcome, impact indicators) they do so to justify the (investment of resources) 40-hour workweek-based salary (OECD, 2013). Productivity should be measured more in efficiency and innovation in achieving outcomes and impacts in solving (business/customer) problems and less in hours worked. The difficulty is to not use time as the primary yardstick to measure productivity. Of course, hours devoted to different problems will be measured, but focusing exclusively on hours worked makes the ingredients more important than the finished recipe.

I recently read an email from a director level leader where they spent considerable time explaining what the core office hours are with several example scenarios of different arrival and departure times, lunch hours and what was acceptable variations to include the scheduling of things like medical appointments (personal okay, family was not) during office hours. This manager (disguised as a leader) is messaging that being present and thus hours worked is what is most important not the actual problems being solved with those hours.

“I’d Say, in a given week, I probably only do about fifteen minutes of real, actual work.” - Peter Gibbons (Office Space, 1999)

Are we paid for our productivity or for our attendance? If the job description describes a five-day, 40-hour workweek as the standard working hours then it is for attendance. There are a couple of points to this statement. First, it is reasonable that the 40-hour workweek has endured partly because it’s the standard measure of a productive workweek. Since salary is connected to productivity – salary is paid in a 40-hour increment. Thus, hours worked is the current measure of productivity. Of note, jobs that require continuous service and/or customer interaction would be primarily measured by hours worked and as such productivity would correlate to hours on the job.

Second, how do you take a bunch of different career fields with different tasks and define a salary for them? Do you look at each primary duty (task) and quantify its value to the bottom line and then pay accordingly? Yes, this is what we do when we associate roles and titles (levels of responsibility, influence and risk ownership share). It is why the senior executive vice president of the company makes more than the junior executive vice president. What the 40-hour increment does, however, is provide a standard of measure for all these disparate job salaries. If we removed the 40-hour increment of measure, there would likely be a lot more debate and ambiguity in deriving a baseline standard of measure.

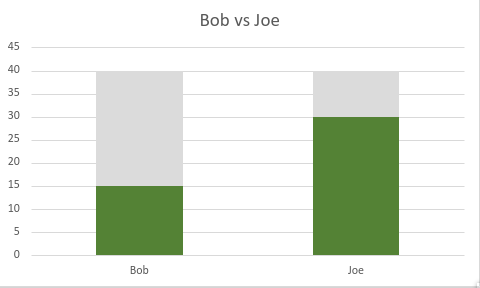

Let us take an example, Bob and Joe are peers at the same company filling the same job role. Bob can complete his work in 15 hours per week, while Joe takes 30 hours to complete his work. Should Bob be paid half as much as Joe since he only works half as much? Should Bob be paid the same amount as Joe since his work outcome is the same? Should both be required to sit in a cubicle for 40 hours per week, despite their tasks can be completed in under 40 hours? If not, should they still be paid for 40 hours if they go home at the 15-hour and 30-hour mark respectively?

The answer for most is Bob and Joe sit for 40 hours in a cubicle and both Bob and Joe fill their time with other things and before you know it – the job requires 40 hours (or more) to complete. If the company wants to acknowledge Bob’s efficiency, they simply give him a better job title and a raise all the while expecting him to be present for 40 hours each week.

Bob vs Joe

Bob vs Joe

The 40-hour workweek pay scale endures not because it makes any rational sense, but because it makes people feel equal in their suffering. It is the measure to equalize employees - everyone is paid for the same 40-hours of time. Since the 40-hour increment of time defines productivity and thus tied to salary – it endures. True, people are still paid different amounts of money for that time, but one’s presence is the visible measure of equality at the office.

It is more likely that comparisons will be made based on office status which is generally derived from job titles. The title of Vice President sounds important, likely accompanied by a higher salary, a parking spot, the right to wear contrasting collar oxfords and suspenders, but still paid based on the 40-hour workweek. Office politicking will be spent jockeying for job titles with better salaries and ultimately status. Imagine a work environment where status is not derived from titles, suspenders or parking spaces, but from the ability to work only the hours required to complete job tasks while wearing canvas sneakers.

The 40-hour workweek is a yardstick. Want to jockey for a better title and salary? Simply put in more hours than everyone else. Earn status through appearing more dedicated and more productive than your co-workers. This relies on the perception that hours worked are equal to productivity to where the formula of more hours worked will equal greater productivity. This is generally false but still endures.

“We’ve got to protect our phony-baloney jobs, gentlemen.” - Governor Lepetomane (Blazing Saddles, 1974)

It is all very simple. Start by being in the group of first arrivals in the office, but not the very first. Being the first is not an observed event by others so it does no good. Go to meetings you do not need to be in, do this until you can offer input in said meetings. Also, share this information from other meetings to the meetings you do need to be in. You will quickly build a reputation for being in the know and active in many aspects of the company. Add to this by (slightly) over-reporting your activities to your team and supervisor. Lastly, be in the group of last departures from the office.

The combination of all the above techniques will increase the perception of your productivity (doing things) and thus the value you provide to the company with their 40-hour workweek payment to you. Or you could just keep your car parked at work like George - just make sure to keep it clean. A word of advice, do not ask Jerry or Kramer to keep an eye on it for you.

The 40-hour workweek is also an accountability tool for managers. Who are the managers? People obsessed with the control of others or of programs, processes and procedures and are the barrier to change and adaptability in an organization needing to pivot. One might call managers the "frozen middle" of any organization. These are the individuals that relish asking you to come in early or stay late or work on Saturday. The attendance-based 40-hour workweek is justification for the existence of managers.

I’m letting my personal experiences cloud perspective on the role of managers as not all managers and front-line supervisors are friction points. Managers can be valuable team leaders, it all really depends on the industry and specific department or role (SCRUM team versus a HR department), and the individual (if they were once a hall monitor in school and named Bill Lumbergh).

“Uh…we have sort of a problem here. Yeah. You apparently didn’t put one of the new cover sheets on your TPS reports.” - Bill Lumbergh (Office Space, 1999)

One solution is to simply drop the 40-hour workweek from our lexicon. If we stop equating a specific measure of time to our work, we can just focus on the actual work and the actual time that work requires. How many of us have completed all our tasks for the day or reached a point where we have no more mental or physical energy to be productive but remain because it would not be acceptable to go home yet. On the flip side, work that takes more than 40 hours opens opportunity for salary renegotiation or re-thinking the what and how of the work being done. I understand this is a very difficult thing to do. The 40-hour workweek is an ingrained cultural tradition and without it the hope of an Office Space sequel dies.

Instead of thinking in terms of salary negotiations, another solution is to think in terms of workweek negotiations. Break down the first principles of the job. Why does the position exist? What are the core tasks? What happens if those tasks are not completed? What elements of the core tasks need to be completed at a regular interval? What is that interval (hourly, daily, weekly)? Do these tasks require interaction with other individuals, departments or customers? Are these tasks time-sensitive or time-independent? What is the most efficient way to conduct those interactions? Essentially agree to meet those obligations without conditions for the rest of the available working hours. Resistance can be mitigated by being available during the remaining working hours virtually (on call). Remember, the 40-hour workweek salary is not just about the tasks performed, but the company having control and access.

A proviso, be careful in translating the answer to these questions into metrics to measure productivity. The tendency is to fall into Goodhart’s Law of when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. Make lines of code a measure and watch all your software bloat; make the number of support tickets closed out and watch the daily close out count increase without measurable impact in satisfaction or long-term resolution of the problem. Before long, upper-management will use these metrics to determine whether whole departments are productive and worth the bottom-line costs. Why do you think all customer service surveys have to be firewall 5’s for them to count positively for the customer service employees?

The other issue is the concept of productivity itself. Start equating salary with productivity instead of with hours worked and we now introduce quotas and the quantification of everything people do. Particularly in the United States we define productivity as doing things - expelling energy. This must be rough for individuals whose job is relation based - quantify goodwill? Good luck. Maybe productivity should be measured not in the number of things one does in a day or any other numeric measure but on impact and value. If the work is impactful, then it is of value.

An example, from science fiction. Suppose that Luke Skywalker does nothing quantifiable in his service to the Rebellion the entire year - except one day he blows up the Death Star. How should he be paid? If we are using the traditional metric of productivity, not very much as Luke has not been a busy body showing hustle generating TPS reports on a regular basis. Now, if we change productivity to not mean doing lots of things and instead define it as impact or value to the enterprise - then Luke should get paid very well or at least a huge bonus. This takes the concept of commissioned sales and expands its application to non-sales roles.

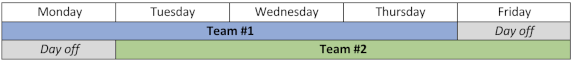

Another idea is shortening the existing Monday through Friday workweek. Consider a Tuesday through Friday schedule in the office. Need coverage on Monday? Split the team with some working Monday through Thursday and the other Tuesday through Friday. Sort of like picking your seat on a Southwest flight, employees can vote on getting Monday off or Friday off to fit their lifestyle. I personally got to enjoy several years of Tuesday through Friday, and it…was…brilliant.

Of course, there are industries where customer interaction or continuous service is required where shorter or alternating workweeks would be more difficult to adopt. Even if a company can achieve continuous coverage, there are potential gaps in coordination that would need to be addressed. Perhaps, a phased implementation plan targeting departments where these schedules can provide the most impact or pilot programs where impacts can be observed and mitigated are good courses of action.

Example 4-day workweek

Example 4-day workweek

A recent U.K. study, where 61 companies tried the four-day workweek out for six months, found 90% wishing to continue the test, 46% citing productivity remained the same, while 34% stated a slight improvement and 15% a significant improvement over the five-day workweek (Fuhrmans, 2023). How could this be? For one company in the study, they found that 20% of the workweek was wasted on unessential meetings, business travel and other office inefficiencies. You fill the space you have – work five days per week – fill up five days with activity to justify one’s existence (we must justify our paycheck and the company must justify the 40-hour workweek). Granted there may be specific roles (recall mention of customer interaction or continuous service roles) that it is difficult to reduce the work footprint by a full day. Consider the Gallop poll cited earlier about individuals that work more than 40 hours per week. Some of those respondents to the Gallop poll probably fall into the category where their workload cannot be reduced. Or can it?

Shrinking the workweek may not just be a matter of cutting out a few meetings – it may require two other things. First, take a hard look at the priority of things. Is there one? If everything is a priority, then nothing is. The fog of seeking status and impressing the boss is a barrier to making any real effort at prioritization (see comments above about measuring metrics). Everyone has a sacred cow and the one cow you want to kill might be the one that ends your upward movement in the company. Everything would be easier if we could just crush all egos.

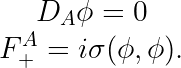

Second, there probably is a more efficient or innovative method of getting after the problem. In 1994, Eric Witten introduced a new equation dealing in Gauge Theory (mathematical theory involving quantum mechanics and the theory of relativity) which was an improvement over Donaldson’s equations because it created a shortcut (Kotschick, 1995).

Seiberg-Witten equations…if you understand this…you’re probably underpaid

Seiberg-Witten equations…if you understand this…you’re probably underpaid

This shortcut from a physicist perspective was a time saver, a more efficient way of getting after the problem. It was an innovation that took deliberate investment of time and energy. If you acknowledge Eric Weinstein’s role in the development of the equations, the effort was also a massive cultural challenge with risk to one’s reputation and career. Taking risks to create innovation may be a dead end in a company that lives and dies by its 10K.

Consider large language models (LLM), a subset of Generative AI, and the potential efficiency gains from incorporating LLMs into the workflow. Effective use of a LLM can increase the processing, analysis, organization, and presentation of data. Generative AI, to include LLMs, can be a more efficient method of getting after the problem - it comes down to being able to ask better questions. Asking better questions requires strong reasoning and critical thinking skills (a la Socrates) - we do not teach these in schools - we teach memorization. Yet, we now have Generative AI for that (in reality ever since we had Google Search).

Do you wonder how George Jetson could only work three hours per day, 3 days per week? He had the 2062 version of Generative AI and the reasoning skills to employ it.

Perhaps another reason for the endurance of the 40-hour workweek – offices and the need to fill them with people. Investment in office buildings is a significant dollar amount for companies. Granted there are just some things that are better suited for in-person interactions – especially wherein one’s work is secretive and compartmentalized (or customer facing). Further, in-person interactions reduce the latency and chaff that online platforms have when you need to connect and collaborate with co-workers quickly (and need to ensure shared meaning is really shared). While it is true that the work-from-home (WFH) movement is shrinking office occupancy rates - If you want workweek flexibility and the location of said work – it probably needs said to not work for a company with a significant investment in iconic office parks.

Or we could just convert those vacant offices into residential living and dramatically increase housing inventory

The 40-hour workweek, the traditional measure of productivity and thus pay, has endured, but should it? The knowledge industry is long overdue change in the measure of productivity for workers (with consideration of the dangers of using other measures as discussed). The WFH movement driving remote and hybrid work as a normal part of the workplace is a ripe opportunity to redefine the measure of productivity from hours worked. It will require a cultural shift in thinking, a revision of our lexicon, and willingness to risk innovation. When CEO’s say they want employees back in the office because that’s where creativity and innovation happen – they are being short sighted – remote work, hybrid work, alternative workweek formats, creating new ways to solve problems and do the work are innovations with the potential for greatly improved efficiency. Take some risks and let innovation happen.

Knowledge Worker Paradigm

40-hour Workweek is an Industrial Age Relic

Salary = Impact or Value

Productivity ≠ Hours Worked nor Quantity of Output

Creativity and Innovation ≠ Physical Space

This Meeting Could Have Been an Email

__________

Ackerman, Andy. dir. 1996. Seinfeld. Season 7, episode 12, “The Caddy,” Aired January 25, 1996, NBC video.

Brooks, Mel. dir. 1974. Blazing Saddles. Warner Brothers, 2002, DVD Disc.

Detroit Historical Society. n.d. “Model T.” https://detroithistorical.org/learn/encyclopedia-of-detroit/model-t

Fuhrmans, Vanessa. 2023. “After Testing Four-Day Week, Companies Say They Don’t Want to Stop.” The Wall Street Journal, February 20, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/after-testing-four-day-week-companies-say-they-dont-want-to-stop-a06089cc.

Judge, Mike. dir. 1999. Office Space. 20^th^ Century Fox, 2018, Blue-ray Disc.

Kotschick, D. 1995. “Gauge Theory is Dead! Long Live Gauge Theory.” Notices of the AMS, Vol. 42, No.3, Mach 1995. https://www.ams.org/notices/199503/kotschick.pdf

Lebowitz, Shana, Ward, Marquerite Ward. 2022. “A History of How the 40-Hour Workweek Became the norm in America.” Business Insider, January 12, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/history-of-the-40-hour-workweek-2015-10.

OECD. 2013. “Development Results: An Overview of Results Measurement and Management.” [Briefing Note].https://www.oecd.org/dac/peer-reviews/Development-Results-Note.pdf.

Rogan, Joe. 2023. “Interview with Eric Weinstein.” The Joe Rogan Experience, recorded February 22, 2023, podcast audio. https://open.spotify.com/episode/7MDxyrrhD7gC7XMRwB0ulv

Saad, Lydia. 2014. “The ‘40-Hour’ Workweek is Actually Longer.” Gallup, August 29, 2014. https://news.gallup.com/poll/175286/hour-workweek-actually-longer-seven-hours.aspx.

Sopher, Philip. 2014. “Where the Five-Day Workweek Came From.” The Atlantic, August 21, 2014. https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/08/where-the-five-day-workweek-came-from/378870/.

__________

© 2023 Jeremy Reynolds, all rights reserved.

Back to Blog Index

innovation